About

- Owner:

- Akin Adekeye

- Born:

- London, to Nigerian parents

- Education:

- Lagos, Nigeria

- Occupation:

- Art collector and dealer, chef and restaurateur

- Passions:

- Art & literature

“Responsibly sourcing and collecting authentic African Art, directly from the artists and communities in which it is produced, has been a lifelong passion. I'd like to share with you my excitement for profound and noble art from across the great continent of Africa.”

Akin Adekeye has travelled widely throughout Africa and been a collector of sub-Saharan African art for more than twenty-five years.

Since 1992 he has sold art through African Arts and Crafts on Drummond Street, London NW1, which, in 2003, became African Kitchen Gallery also housing an award-winning restaurant (Trip-Advisor Hall of Fame 2015-19).

Akin decided to launch theafricanartcollection.uk as an online art catalogue in 2020 in order to share images of this exquisite collection with people from all over the world, and showcase the extraordinary talents of many African artists, most of whom have been purchased from directly. Akin has often travelled to far-flung places, such as Mbiti in Kenya, to pay a fair price to artists for their work.

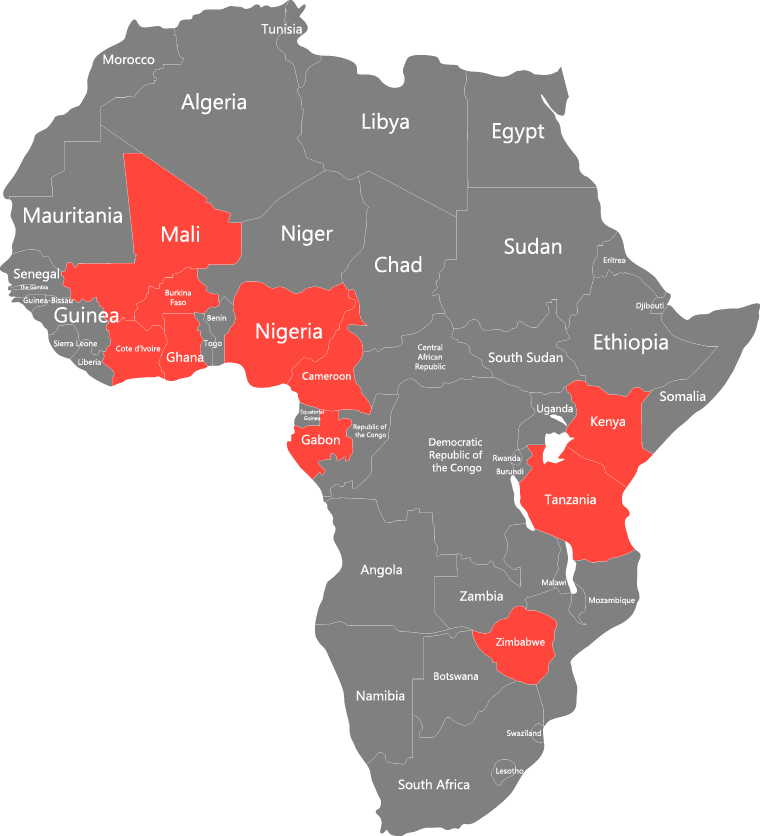

African Art & Peoples

- Area:

- 30,370,000 km2

- Countries:

- 54. Though controversial, this figure is supported by the United Nations and other international bodies

- Population:

- 1.4 billion

- Languages:

- ~2000

Shona Sculpture

Shona sculpture is the name given to a modern movement of stone sculpting in Zimbabwe. The word 'Shona' refers to a group of tribes with closely related languages and cultures predominantly in Zimbabwe.

During its early years of growth in the 1960s and 70s, the nascent ‘Shona sculpture movement’ was described as an art renaissance, an art phenomenon. Critics and collectors could not understand how an art genre had developed with such vigour and originality.

Shona artists draw on their belief that nothing which exists naturally is inanimate, that everything, living or not, has a spirit and life of its own. These spirits are often represented in Shona art.

Artists display a high degree of integrity and spontaneity, never copying others. Still working entirely by hand, they continue to be unconstrained by external ideas of what ‘art’ should be. The sculptures they carve speak of essential human experiences such as grief, elation, humour, anxiety, and spiritual quest.

Many Zimbabwean artists now make their living from full-time sculpting and, as many museums will attest, the best can stand comparison with famous contemporary sculptors anywhere in the world.

Most Shona sculptures are carved from a range of stunning Serpentine stones – black, green, brown, spring stone, ‘opal’ and cobalt and from semi-precious verdite.

Ashanti Mask / Akua’ba Fertility Doll

Since their first king, Osei Tutu, the Ashanti (or Asante) nation prospered in what today is Ghana. Fierce fighters, Ashanti were one of the few African peoples and states that seriously resisted European colonizers, their warriors uncowed by sniper rifles and seven-pounder guns.

Ashanti are a mainly matrilineal society, the line of descent traced through the female. Historically, this mother progeny relationship determined land rights, inheritance of property, offices and titles. Ashanti culture, flourishing in line with the power of the state, was famous for gold and brass craftsmanship, wood carving, furniture, and brightly coloured woven cloth, called kente.

Ashanti masks were believed to bridge the gap between the spiritual physical realms, bringing the spirits of the ancestors and other entities to life through dance. The greatest and most frequent mask-wearing ceremonies of the Ashanti recalled the spirits of departed rulers with offerings of food and drink, requesting the rulers’ favour for the common good, called the Adae.

According to Ashanti legend, the bearer of a carved wooden Akua’ba fertility doll would give birth safely to a beautiful perfect baby. Fertility dolls represent youth and fecundity and are consecrated by priests. The lower section of fertility dolls is often similar in shape to a Kamitic symbol known as the Djed, which according to legend is the backbone of the God Ausar. After influencing pregnancy, akua’ba are often returned to shrines as offerings to the spirits who responded to the appeals for a child.

Bambara Mask, Chiwara

The Bambara peoples, at the height of their splendour in the XVII century, live in central and southern Mali. They believe in the existence of a god called Ngala, creator of all things, who has 266 sacred attributes and maintains order in the universe. Ngala coexists with another deity, the androgynous Faro, who bestows humans with their qualities and allows vegetation to grow. Today ‘Bambara’ is a pejorative term used by some Muslims to designate the nonbelieving ones.

Bambara masks are used during rituals of initiation, and during other events such as weddings, births, circumcisions, deceases, funerals and purifications of objects and beings. Bambara masks receive offerings and sacrifices, and they are often solemnly buried following a rite when their role of intermediation is complete and they have lost their sacred character.

A Chiwara is a ritual object or mask representing an antelope used by the Bambara at initiations involving ceremonial dances and rituals that are primarily to teach young men social values and agricultural techniques.

Bamileke / Bamu Mask

The Bamileke are the largest ethnic group in Cameroon and inhabit the country's West and Northwest Regions. Bamileke settlements are organized as chiefdoms. The chief, or fon, is considered the spiritual, political, judicial and military leader and ‘father’ of the chiefdom and is greatly esteemed by his people. The powers of the fon ensure the protection of his people and guarantee the fertility of the fields and the fecundity of the women.

Bamileke and Bamu masks are made to the honour the king and or important chiefs or fon. Masks are thus regarded as objects of power and are displayed during important rituals and ceremonies, principally to commemorate and celebrate the royal ancestors of the present fon. The masks’ abstract patterns are symbols of great wisdom, the cowry shells depicting wealth. The masks are also used during planting and harvesting, for the annual festival of the dry season, at the opening of the royal hunt and, historically, for expeditions of war.

Bwa Mask

The Bwa people are native to Burkina Faso and live in autonomous communities, each led by a council of male elders. They rely on their community standards and customs rather than on laws. The three professional castes within Bwa society are farmers whose most important crop is cotton, musicians who play hand-carved flutes and beat drums, and blacksmiths who craft masks, utensils and jewellery. Animists by belief, the Bwa also worship the creator deity Wuro, a god who designed the earth with the intention of establishing balance. Their art work is primarily used for animist practices.

Bwa are particularly famous for their masks which, along with sceptres and diverse body adornments, are used in ritual dances to represent different spirits. Bwa young people going through initiation adorn and praise the masks that are being performed as a group. These mask performances are not gender specific. According to the Bwa’s Nuna religion, the spirit Lanle’s power is manifested through the wooden masks. The Southern Bwa are known for their tall and extraordinary plank masks, known as nwantantay. Mask performances generally take place in the dry season between February and May.

Dan Mask

The Dan people live in West Ivory Coast and Liberia. Historically the Dan lacked any central governing power with social cohesion maintained through a shared language and intermarriage. Each village had a headman who earned his position through hard work in the fields and as a hunter. Surrounding themselves with young warriors for protection from invading neighbours, the headmen exchanged gifts with other chiefs in order to heighten their own prestige. The Dan believe that all creatures have a spirit soul, du, which is imparted into humans and animals from the creator god, Xra, through birth. Some du remain bodiless and will choose a young man to dance at ritual ceremonies, utilising a mask to illustrate the spirit's embodiment.

Dan people refer to masks as gle or ge, referring to both the physical mask and the spirit the mask is believed to embody during masquerade performances. The most sacred Gore ancestral masks served to protect the young initiate against destructive or evil forces from the time of initiation, until he one day enters the spirit realm. Once the male mask dancer dons the mask, he is transformed into a spirit. He goes into a deep trance during these rituals, bringing forth messages of wisdom from his forebears which prescribe a way of life that will lead to the village’s longevity, health and prosperity.

Dogon Statue

The Dogon inhabit the central plateau region of Mali and part of neighbouring Burkina Faso. With no centralized system of government, they live in villages composed of extended families whose head is the senior male descendant. The Dogon tribe are known for their religious traditions, ritual dances, their masks and wooden sculptures and their architecture, and for their remarkable astronomical knowledge. Dogon worship ancestors and communicate to them through Binu spirits which often make themselves known to their descendants in the form of an animal that becomes the village’s totem. Dogon believe that death came into the world as a result of primeval man's transgressions against the divine order.

Dogon wooden statues honour a family's real and mythical ancestors and the spirits responsible for the fertility of both land and people. Scholars agree that many Dogon statues were created for shrines.

Fang Mask

The Fang are spread over a vast area along the Atlantic coast line of equatorial Africa and inhabit parts of Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon. They were fine warriors and hunters and cultivated a reputation for cannibalism in order to repel attacks from outsiders. The Fang kinship system is strongly patrilineal, with large, patriarchal families and marriage-related clans. Largely Christian cocoa farmers since the Second World War, the Fang have seen their native crafts, including reputed wood carving and iron work, largely disappear under Western influence, notwithstanding that they have preserved their history through musical oral tradition. The religion of Fang centres around ancestors who are believed to wield power in the afterlife.

Fang wooden masks and idol carvings are on display at numerous museums around the world. Masks were worn for hunting during the initiation of new members, to honour ancestors and during the persecution of wrongdoers and sorcerers. During these ceremonies masqueraders, clad in raffia costumes would materialize in the village after dark, illuminated by flickering torchlight.

Guro Mask

The Guro tribe, from Ivory Coast, were originally known as the Kweni tribe prior to French colonisation. Today they are mainly agriculturists whose crops include plantain, rice, yams, palm oil, coffee, cocoa, and cotton. The Guro religion has many deities. An ‘earth master’ makes sacrifices to ‘earth deities’ for the benefit of the village’s inhabitants. Each village has a diviner who is consulted on important decisions.

Guro tribal masks honour protective spirits or zuzus. Many represent the spirit of Gu, the wife of Zamble a supernatural being. Gu is often depicted as elegant, graceful, serene and beautiful. Guro masks, delicately crafted and colourful and sometime combining human and animal forms, are used at sacrificial gatherings, funerals, and celebrations.

Ibibio Mask

The Ibibio people are Kwa-speaking people who occupy the palm belt in the southeast Nigeria`s Akwa Ibom state and are regarded as the most ancient of all the ethnic groups in Nigeria. Traditional Ibibio society consists of communities made up of large families and ruled by a legal and religious head known as the Obong Ikpaisong. The most important Ibibio myth holds that the creator of all things, Abassi, was persuaded by his wife, Atai, to let humans live on earth on the condition that she also send death and discord to keep the people in their place and control their numbers. Worship of the ancestors, responsible for the tribe’s welfare, is crucial to Ibibio religious culture and often involved sacrifices made at the ancestral shrine.

In Ibibio ceremonies commemorating the deceased, the most common mask, Mfon, represents a beautiful spirit who has attained paradise. Mfon feature in daytime burial festivities honouring the recent dead, and at annual agricultural festivals. They can also represent the souls of unnamed ancestors whose positive influence is welcome among the living.

Igbo Mask

The Igbo live chiefly in south-eastern Nigeria and speak Igbo. Before European colonization, the Igbo lived in autonomous local communities, but by the mid-20th century such a strong sense of ethnic identity had developed that the Igbo-dominated Eastern region of Nigeria tried to unilaterally secede from Nigeria in 1967 as Biafra. Today, in rural Nigeria, Igbo people work mostly as craftsmen, farmers and traders. The most important crops are yam, cassava and taro. When European colonisers appeared in the mid-nineteenth century, the Igbo people were hesitant to convert to Christianity, believing that the gods of their native religion, most notably the supreme deity Chukwu (great spirit), would bring disaster to them. Today, however, the Igbo have adopted Christianity more than any other ethnic group in Africa.

Masks have been used for different purposes within Igbo culture in both historic and modern times. Masquerade ceremonies include initiation rituals during which Igbo boys become men and rituals to maintain connections with the deceased. Masks become physical embodiments of those no longer living, facilitating the flow of blessings and knowledge between generations. Ceremonies promote communal healing, continuity, connection and wellbeing as the living are able once more to interact with those that have been lost.

Punu Mask

The Punu encompass many tribes. Inhabiting the interior mountain and grassland areas of Gabon and the Republic of the Congo, they speak Yipunu or Yisira. They live in independent villages divided into family-based subgroups. Their most important mythological stories centre on Nyambye Mbumba. the ‘Serpent God’, creator of the universe. Famous for their tribal dances, many of which are performed on stilts, the Punu feared evil spirits who cause illnesses that can only be cured by special rituals to cast away the evil spirit's work.

Punu masks are worn during ritual masquerade dances and represent the spirits of male and female ancestors. The white face of many masks from Gabon represents the soul of an ancestor. Punu masks nowadays are used to entertain audiences during festivals and celebrations, except on the rare occasions that they are employed for a ritual function. Some natural wood-coloured masks have a judicial function, and are used by chiefs to seek the judgement of the ancestors in order to solve problems.

Senufo Mask

The Senufo are a West African ethnolinguistic group. They consist of diverse subgroups living in a region spanning the fertile prairies of northern Ivory Coast, south-eastern Mali and western Burkina Faso. They are, for the most part, peace-loving farmers, each of their autonomous villages connected to one another culturally rather than politically. The Senufo are animists, believing that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. They worship their ancestors, and believe in a Supreme Being, who is viewed in a dual female-male: an Ancient Mother, Maleeo, and a male Creator God, Kolotyolo. The ‘Ancient Mother’ is so powerful that she has to be judiciously approached through the intervention of lesser gods.

Senufo masks are created by specialist artists who live apart from the rest of their village. They enjoy a high status in their society as their masks and sculptures are believed to facilitate communication between the living and the village’s dead ancestors. The masks, usually combining animal and human features in a single design, are used not only to commune with ancestors but also during the rites of young men coming of age.